SLAC and Stanford researchers advance understanding of a key celiac enzyme

Wheat and other sources of gluten can spell trouble for people with the disease, but new findings could aid the development of first-ever drugs for the autoimmune disorder.

Celiac disease affects around one in a hundred people worldwide, and those that have the autoimmune disorder have no choice but to stick to a gluten-free diet forever – at the moment, doctors have no other way to treat the illness.

Now, those seeking a treatment could get a boost: A new study from researchers at Stanford University and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the U.S. Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has revealed previously unseen details of a key enzyme behind the disease. The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

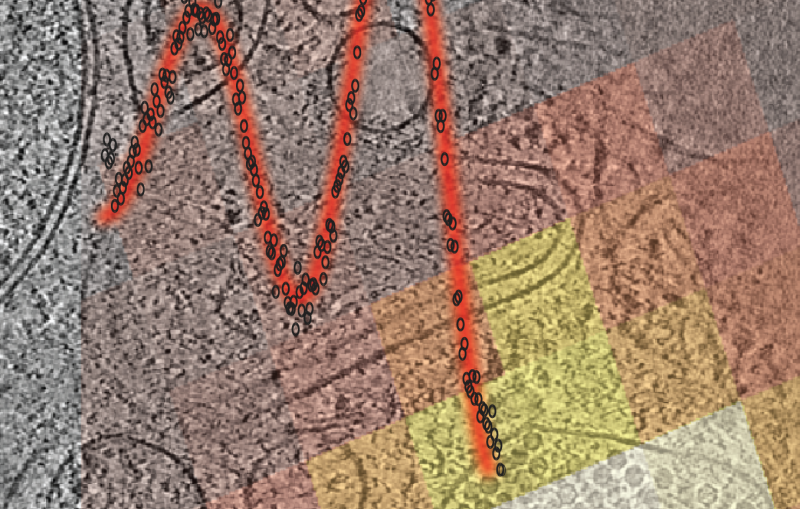

Celiac scientists have known for several years now that the enzyme in question, transglutiminase 2 (TG2), could trigger an immune response in the presence of gluten and calcium ions, leading the body to attack its own intestinal tissues. What has been less clear is exactly how TG2 works and how best to target it with drugs — in part because scientists have only had a limited understanding of the enzyme's structure. Previous studies have mapped out TG2's inactive, "closed" state and its active, "open" state, but how it transformed from one to the other or what happens in the interim remained unclear.

To address that problem, Angele Sewa, a graduate student in chemistry and biochemistry in Stanford chemist Chaitan Khosla's lab and a fellow in the Sarafan ChEM-H Chemistry/Biology Interface Training Program, and Harrison Besser, a student in Stanford's Medical Scientist Training Program, first worked to create complexes of TG2, calcium ions and gluten-like substances that could reveal in greater detail how TG2 works. Sewa next grew crystals of those complexes and worked with SSRL lead scientist Irimpan Mathews to understand their structures using X-ray macromolecular crystallography.

The effort was a success: Several of the crystallization concoctions the team came up with captured TG2 in a previously unobserved intermediate state between its active and inactive states. Analyzing the structure of this intermediate state, the researchers wrote, uncovered a wealth of details about how TG2 interacts with gluten and calcium, helping to make sense of previous results about TG2's behavior as well as identifying specific sites within TG2 that play key roles in its activity.

While researchers are already developing drugs targeting TG2 for celiac disease and another TG2-related disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, "this study provides fundamentally new structural and mechanistic insight into how TG2-inhibiting drugs work," Khosla said. "These insights can be used to make better drugs against this target."

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology program is supported by the DOE Office of Science and the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Citation: Agnele S. Sewa, et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 3 July 2024 (10.1073/pnas.2407066121)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.